Heaven knows there are plenty of established techniques, worksheets, strategies, structures, and whatever-elses out there for outlining a story. But, you know, sometimes you just wanna try a new one. And why not?

I think those very regimented outlining devices can work really well for a lot of people and a lot of stories, but sometimes you might not want to stick quite so cleanly to a pre-established format. Maybe you want to write something that focuses more on exploring themes than it does on tracking narrative arcs and adhering to a three-act structure, or maybe you just want to be able to express your vibes and ideas in a less formalised kind of way.

For me, beat sheets and the like can be really handy for some kinds of story, but I don’t always think they’re the right way to achieve what I’m after. Sometimes I want a story to feel a bit cleaner, neater, more structured, and sometimes I just don’t think that’s the effect I want to create.

This is a technique I’m sure someone else has come up with elsewhere, but I’ve never seen it, so here it is. It’s what I used to write my first three novel drafts (one of which became Each Little Universe, and the other two are currently unpublished but we’ll get there!), and I’ve never really thought too hard before about exactly how I did it because it felt sort of accidental at the time. And I kinda like that, actually. If you’re into that kind of creativity that feels less like you’re making a science out of it and more like you’re just letting ideas flow and become their own things, maybe this’ll work for you.

Step 1: collect everything.

If you’re anything like me, you’re constantly thinking of bizarre little tangents, scenes, seeds for characters. I went for a walk earlier and saw:

- a tree with a cool forked branch that made me start thinking about a little town built in a huge tree

- two birds chasing each other around that made me think of one very curious person incessantly bothering another to find out what they’ve got in their pocket (it’s something completely mundane)

- a man repeatedly trying to kick a football into a basketball hoop, which made me imagine a sort of Sisyphean scenario in which someone is bound or compelled to do the same pointless thing over and over again

Now, generally I just forget most of those things the minute I think them, which is… like, fine, I guess, but not the most helpful. So, when I can, I shove them all into a note on my phone or a Google doc. Yeah, it’s completely unorganised, but it’s somewhere I can find and review them later.

The end result of this step is that I have a lot of, like, sub-three-sentence ideas, vignettes, little images, character motivations, fantasy elements, lines of dialogue, and all kinds of things lying around. So that’s all I’m really encouraging you to do here: whenever you think of anything, even if it feels totally disconnected from an actual story idea, write it down.

Step 2: look for common themes.

When I’d been doing this for a long time, it occurred to me that maybe I could actually do something with all this disparate nonsense. So I had a look (a very long scrolling look) through the note I had with all the different little snippets that had popped into my brain unsolicited.

From there, I picked out some of the ones that shared a common theme. For Each Little Universe, that theme was love: love of a friend, of a slice of pizza, of a video game, of a cat that wandered into your house one time. (For another novel, one I’ve been working on for a long time – and sincerely hope to actually finish one day but it’s personally important to me or something annoying like that so it’s hard – that theme was identity in all its various aspects.)

Importantly, I wasn’t looking for stuff that stuck too closely to that theme. In fact, some things weren’t really relevant at all, but I could sort of see how they could provide different angles and lenses to take a look at the theme. My goal wasn’t to have something incredibly coherent and cohesive but to give myself a whole range of Story-Includable Things that, taken together, could serve as this big wide look at love (or whatever theme) in all its varying aspects.

You might find it more efficient to start grouping stuff by theme while you’re adding to your list – that is, whenever you have a new snippet, immediately drop it in the relevant spot rather than listing everything in a completely disorganised way and trying to categorise them after the fact. You could have different documents for different themes, sections in the same document, or even look at note-taking software that allows you to sort things into different buckets or folders.

These days I use Obsidian for my writing stuff and Notion for work; both allow me to create structures to organise my thoughts a bit more cleanly than simple notes, as well as letting me do neat things like link from one file to another. It’s more useful than I would have thought to actually find a tool that suits the way your brain works rather than just jotting things down. Unless just jotting things down is best for your brain, which is entirely valid!

Step 3: Decide what you really want to say about your theme.

So you’ve got a theme (maybe two, but I think having one central one is kind of key so you’ve at least got some coherence!) and a bunch of little snippets of ideas related to that theme.

Now it’s time to think: OK, what do I really want to say about this?

For Each Little Universe, I decided that what I wanted to say about love was that there are a lot of kinds of love and they’re all just as valid and important as one another. That’s sort of the key thesis statement of that book, and pretty much everything that happens in it does so in order to provide an opportunity to explore that notion. It’s not a romance novel or a love story, but it is fundamentally about the love and connections that people have with one another and in themselves.

There’s another question that comes with this: what kind of conflict or opposing force will allow you to tell a story that explores that? To take ELU as the example again, I thought that if I wanted to explore the power of love and humanity, the best thing to pit against it would be the vast, uncaring, inhuman forces of the cosmos. What better way to show just how strong these bonds are than by having them stand up against the universe itself?

Step 4: Make it so.

Yeah, OK, so at this point you might actually want to refer to another outlining method, because I’ve got very little concrete advice about how to take what you’ve got and turn it into a real story structure.

For me, since I do this because I’m feeling more of a vibe and an exploration of theme than a tightly-plotted formally structured thing, I think a beginning, middle, and end is probably enough. Pick strong images that state your theme.

Your beginning should set out what your theme is and demonstrate it; your middle should complicate, twist, or otherwise play with the theme you started with; your end should resolve this (or not, if you like leaving things hanging, which is fine!) and just kind of bring all the points you’ve made together into a lasting sentiment, the Big Thing you’re leaving your reader to ponder upon.

Step 5: Cram in all those snippets!

Now’s your chance to fit in as many of those snippets as possible.

“But, Chris,” you might say, “won’t that be kind of overdoing it? Won’t it be messy? Won’t it feel just like Too Much?”

To which I say, “well, yes, maybe.” It definitely can feel that way. And sometimes that might be the aesthetic you’re going for, a kind of oversaturated maximalism in which you simply jam in as many things as you possibly can and let them have fun with each other.

But you probably want it to feel a bit more cohesive than that, which is why it’s now worth taking the time to work out where each of your snippets on the theme might fit into the story.

I find that this part – looking at the non-sequitur sentences I wrote down for no particular reason and thinking about them in the context of this story and theme I’ve just developed – actually helps to fill out the journey from beginning to end. It gives me some suggestions for what goes between those two points, kind of organically suggesting characters, scenes, and whatnot to form the bulk of the text.

When you’ve done this, you basically have a theme, a broad-strokes journey, and a bunch of fun things you can go through on the way. It might well take some more thinking about, but you should at least have a skeleton of something that makes a strong statement about a theme and explores it in different, interesting ways.

And… that’s kind of it!

It’s not a science

Don’t feel you have to stick too closely to this approach. Heck, I’m describing my approach and I’m sure I never treated it as something I had to actively focus on sticking to. Take what works for you, combine bits of it with other planning techniques, whatever. If any part of it feels useful, take that and leave the rest!

If it does work for you, though – or indeed if you’re aware of anything similar that other people have talked about and I’ve just not come across – let me know! I’d be fascinated to hear what other writers make of it. Maybe it only works for my brain!

More tips on structuring stories, creating characters, livening up prose, and more are available on my tips hub.

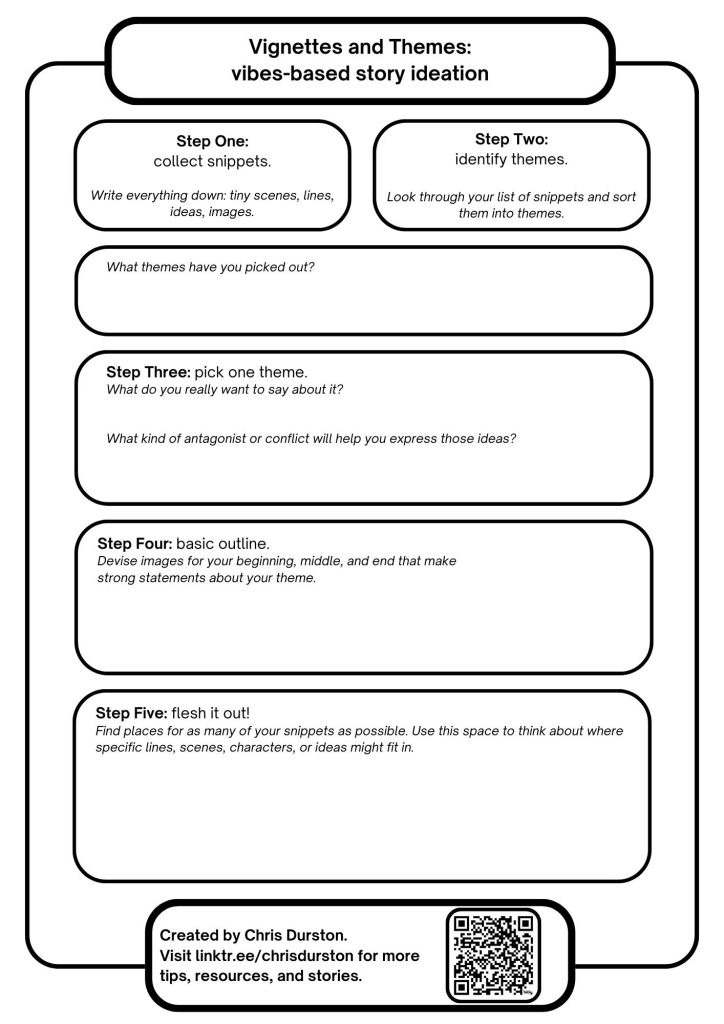

Get the worksheet

I’m terrible at making worksheets and stuff, but I figure if I’m claiming to have a process, people really dig worksheets, right?

So I’ve made a very basic sheet you can use to follow this process for yourself! Download it here: PDF version – JPG version.